Let’s talk about Mindful Based Parenting. Specifically, what it means and how it can help bring calm to the chaos of parenting. I will share some key mindful parenting strategies to help you incorporate this new practice and a checklist to keep you on track. The idea behind this Mindful Parenting Checklist is to help you adopt some new parenting habits that will make your parent-child relationships less reactive. The practice of mindfulness can help your parenting and family time become more purposeful and enjoyable.

Before, I jump into the Mindful Parenting Checklist, I want to answer the basic question, “What is mindfulness”? According to Jon Kabat-Zinn, Ph.D., who credited with initiating the popularity of mindfulness in the West, “Mindfulness is actually a way of connecting with your life…paying attention on purpose in the present moment, non-judgmentally.” It is basically the idea that we need to be more in the present. We should pay attention to the moment, rather than worrying about the past or the future. It is a way of being focused around awareness of the current time rather than anxiety of the future or depressive rumination.

What is Mindful Parenting?

So with that said, “What is mindful parenting”? It is the practice of applying the same principles of attention to the present with our children. It was well put by Jon Kabatizinn in the Huffington Post, “Mindful parenting involves keeping in mind what is truly important as we go about the activities of daily living with our children…For us to learn from our children requires that we pay attention, and learn to be still within ourselves. In stillness, we are better able to see past the endemic turmoil and cloudiness and reactivity of our own minds, in which we are so frequently caught up, and in this way, cultivate greater clarity, calmness and insight, which we can bring directly to our parenting…Just bringing this kind of sensitivity to our parenting will enhance our sense of connectedness with our children.”

Mindful Parenting Quotes To Inspire You

I read a quote once that I will always remember because I thought, “You know what? That is so true. And my being there fully in the moment and really listening to my child matters.” I hope it inspires you too. Here it that mindful parenting quote:

“Listen earnestly to anything [your children] want to tell you, no matter what. If you don’t listen eagerly to the little stuff when they are little, they won’t tell you the big stuff when they are big, because to them all of it has always been big stuff.”

― Catherine M. Wallace

Here is another of my favorite mindful parenting quotes:

“Use anger as a wake-up call to unmet needs.” -Marshall Rosenberg, Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life: Life-Changing Tools for Healthy Relationships

This quote is so instructional and so useful for all of our relationships. Whether our child is feeling angry or whether we are feeling angry, it is a good time to pause. Take a moment to examine why they (or we) feel that way and what needs are going unmet. This will allow you or your child to communicate feelings and needs in a productive way.

Another great mindful parenting quote:

“Getting in touch with conscious behavior we change our attitudes so that we are not ruled by instincts, habits, and someone else’s beliefs.” -Nataša Pantović, Conscious Parenting

This one speaks to make conscious decisions in our parenting rather than reacting. For example, you child is not doing what you said. You could assume they are defiant and need to be punished. Or, instead, you could question your child further to see what is upsetting them and causing them to ignore your request.

One last conscious parenting quote:

“The way we talk to our children becomes their inner voice.” – Peggy O’Mara

This quote captures the conscious parenting meaning which involves being mindful, present, and intentional in raising children. Our words have power so we should chose positive, motivational ways of speaking to our children.

Conscious parenting aims for a more authentic, individualized approach to parenting by understanding the underlying causes of one’s reactions, while mindful parenting seeks to create a peaceful, attentive, and compassionate parenting environment through mindfulness practices.

Mindful Parenting Techniques

If that was too much of a mouthful, mindful parenting, in its simplest terms is about awareness. It brings your awareness to your needs and your child’s needs in the present moment staying focused on that. Mindful parenting is the slowing down of your thoughts and by cleansing your mind. It is about thinking less and panicking less and being there in the moment for yourself and your child more. To begin the practice of mindful parenting techniques, you may find it useful to write a personal mission statement. Doing so can help you determine what is most important to you in your family life.

Mindful Listening

- Practice: Give your full attention when your child is speaking. Listen without interrupting, judging, or thinking about your response. Focus on understanding your child’s feelings and perspective.

- Benefit: This creates a strong connection with your child, making them feel heard and valued.

Non-Judgmental Awareness

- Practice: Observe your thoughts, emotions, and reactions without labeling them as good or bad. Apply the same non-judgmental awareness to your child’s behavior, focusing on understanding rather than judging.

- Benefit: This reduces stress and creates a more accepting and nurturing environment.

Mindful Pausing

- Practice: When faced with a challenging situation, pause before reacting. Take a moment to consider your response, ensuring it aligns with your values and the needs of your child.

- Benefit: Pausing helps prevent impulsive reactions and promotes thoughtful, compassionate responses.

Compassionate Communication

- Practice: Speak to your child with kindness and empathy, even during difficult conversations. Use “I” statements to express your feelings and needs without blaming or criticizing.

- Benefit: This fosters a safe space for open communication and encourages your child to express themselves honestly and respectfully.

Basically, we can all get caught up in the hectic schedules and stress of daily life. However, practicing mindful parenting strategies can help make life calmer, happier, and healthier. We can turn a moment of stressed out panic to get out the door and anger at the kids for not being ready into speaking and moving in a purposeful way that communicates our expectations without panic, stress, judgement, and fear. Mindful parenting will still encounter times of strong emotions and conflicting needs but because of your connection to the present moment for you and your child, your actions and words will likely have more kindness and wisdom in them. This mindful approach breeds more positive behavior and potential benefits for both parent and child.

Mindful Parenting Example

“Say you’ve put a lot of energy into making dinner after a difficult day, and your baby starts screaming and is inconsolable just when you are about to sit down and enjoy it. That’s a perfect opportunity to bring mindfulness right into that moment and see how attached you may be to having a peaceful dinner. What are your options? You can flip out and be immature and not be in resonance with whatever your child is experiencing, or you can realize this it what it means sometimes to have baby or a toddler. Life itself is the curriculum. When you give up your attachment, you won’t relate to your child with resentment.” –Gaiam.com

Next time you find yourself in a challenging situation, try responding in new ways. A parent’s ability to help their child with emotional regulation may be limited if he or she has not learned to do so themself. The first step in avoiding negative parenting behavior may be to use a mindful way of calming oneself before demanding that your child is calm. Simple ways include taking a deep breath and trying to breathe out your frustration before responding. Having an emotional awareness to our own reactions will help us be more understanding of our child’s feelings and needs as well.

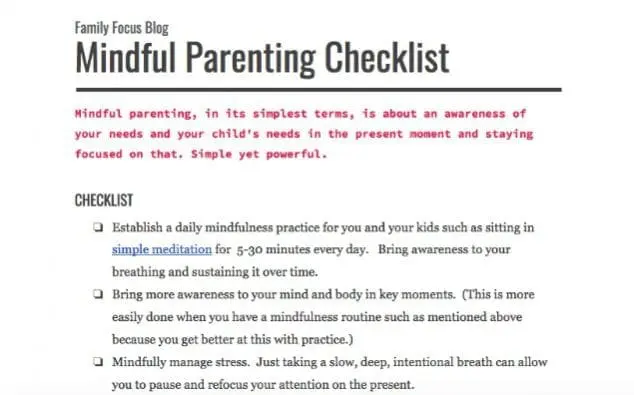

Mindful Parenting Checklist To Help Guide You

The Mindful website, reports that, “according to new research, children who experience mindful parenting are less likely to use drugs or get depression or anxiety.” It is generally agreed that mindfulness and mindful parenting are successful at promoting well-being in several ways. To bring mindful attention and awareness into your interactions with your child really seems to set the stage for you to be a good parent.

Here are some ideas to help you become a more mindful parent. I have presented them in checklist format so you print it out and go over it occasionally. Otherwise, we all know that it can be hard to remember everything and to implement new habits. The Mindful Parenting Checklist will help you make the progress that you want to make.

How To Bring Mindfulness To Parenting

- Establish a daily mindfulness practice for you and your kids such as sitting in simple meditation for 5-30 minutes every day. During your meditation practice, bring awareness to your breathing and sustaining it over time.

- Bring more awareness to your mind and body in key moments. This is more easily done when you have a mindfulness routine such as mentioned above. You get better at this with practice.

- Mindfully manage stress. Just taking a slow, intentional, deep breath can allow you to pause and refocus your attention on the present.

- Be mindful of what’s unfolding in your life and your children’s lives. Honor your needs and their needs as best you can. Don’t get mindlessly caught up in reactions to surface behaviors.

- See young children as they are, not as who you want them to be. Meet your child with more acceptance.

- Cultivate kindness and compassion in the moment for yourself and for your child.

- Be in the present with open-hearted, non-judgmental attention.

- Be less attached to outcomes.

- When a conflict or difficult situations occur with your child, pause and take a breath. Ask yourself, “Am I just reacting here or am I responding with purpose?”

- Mindful parenting should include listening carefully to a child’s viewpoint even when disagreeing with it. Allow them the opportunity to express their own feelings.

Printable Checklist

I don’t think you will use this checklist every day indefinitely. However, I do think you will find it useful to use everyday for about a week. It will help you get into a better routine. Then you can reduce to once a week for awhile to help make sure you aren’t forgetting anything.

Again, this Mindful Parenting Checklist is intended to help you implement new habits into your daily routine. It is not something you should stress over. Don’t try to check off every box, every day. Rather it is just a useful tool for your mindfulness training. It will cause you to slow down and be present in the moment. When used properly, it should help with stress reduction and managing negative emotions. Mindful awareness in everyday life will lead to positive changes and less anxiety.

The image above is a partial capture of the full printable Mindful Parenting Checklist. You can go to google documents and print the whole page there.

Parenting At Its Best

It has happened to all of that we find ourselves going through the motions. As your child talks to you, your attention may wonder and you are off thinking about the stuff you need to get done. Wouldn’t you rather be enjoying the experience of being with your child? Be there to truly listen and respond with joy, humor, or just true attention. Mindful parenting isn’t just for when things are going wrong, it is for when things are going right too! It is being there in that moment and giving your child your full attention. It seems so basic but in this multi-tasking, multi-device, over-stimulation world, we have to get back to basics sometimes.

Your child wants your attention more than anything else. In fact, we all appreciate those moments when a person is truly giving us their full presence. It is the greatest gift. Make your mindful moment awareness for good things too!

Conclusion

So tonight, when you tuck your child in, try mindful parenting. Put aside your worries and preoccupations and just enjoy your exchange with your child. When you look at them, really see them. When you listen, really listen. And when you tell them you love them, think about how much you really mean it. I bet you enjoy mindful parenting! It feels good.

If you are interested in mindful parenting but you feel like you really need some help, you may want to check out MamaZen. It is the #1 mindful parenting app for mothers who want to raise happier kids!

Related Posts:

Solutions For Parenting Challenges

Lisa Bradburn says

What a wonderful and thought-provoking blog. Be present, listen earnestly…the quote from Catherine Wallace is absolutely spot on. We were just listening to a discussion about some schools introducing mindfulness for children- I couldn’t agree more with that idea. These quotes emphasize the importance of mindfulness, connection, and the impact parents have on their children’s development through their actions, words, and presence. Thank you for sharing your thoughts!

Summer Cox says

Your blog just changed an interaction with my 2 year old from my threatening to take away his toy if he hurts his baby sister, to practicing calling Mommy for help if she’s starting to mess with his stuff. You’ve blessed my day. Thanks so much.

Scarlet says

And you have blessed my day with your kind words:) Thank you.

Alex Wright says

Great post! I especially like this part in your conclusion, “Put aside your worries and preoccupations and just enjoy your exchange with your child. When you look at them, really see them. When you listen, really listen. And when you tell them you love them, think about how much you really mean it.” Very inspiring! I hope I can apply some of what you’re saying. Reading your post reminded me of something I heard once- “When little people are overwhelmed by big emotions, it’s our job to share our calm, not join their chaos.”

Senior says

This is a fantastic piece! Your thorough research and engaging writing style make it a must-read for anyone interested in the topic. I appreciate the practical tips and examples you included. Thank you for sharing such valuable insights.

Paint Colors says

Great blog on mindful parenting! The quotes and checklist provide such valuable guidance for staying present and positive with our children. It’s a wonderful resource for parents looking to cultivate a more mindful approach. Thanks for sharing!

Cutting Edger says

I love these mindful parenting quotes and mindfulness checklist! They’re a great resource for staying focused and positive. Thanks for the inspiration!

Mamawithlove says

This mindful parenting checklist is such a great resource for staying present and fostering a positive parent-child relationship. I love the focus on pausing before reacting and really listening to your child’s viewpoint.

Kidzonia says

These quotes and the checklist are a great reminder of the importance of mindful parenting.